PCO: A New Model of Ownership

Matt Prewitt, Jack Henderson

February 20, 2024

Partial Common Ownership (PCO) is a flexible template for reconfiguring property relations, which has inspired many of us at RadicalxChange because it opens the door to a different kind of conversation about capitalism.

Most other calls to rethink capitalism recognize as we do that important sources of value and productivity are “upstream” and non-marketized factors like physical and social infrastructure, invisible work within families and communities, etc.—which are much more distributed and networked than the wildly distorted and inequitable outcomes in capitalism lead us to believe.

But they do not question conventional ownership itself. Instead, they usually seek to either divide and fractionalize ownership (i.e., give more or different people a share of conventional ownership); or consolidate ownership (i.e., place it in the hands of some representative of the public, like the state). Both of these approaches often do good, but they are only band-aids. Fractionalizing ownership just “spreads around” the same old extractive incentives of conventional ownership, while consolidating ownership “puts all the eggs in one basket,” intensifying the risks of institutional capture and illegitimate representation.

PCO takes a different path. It is based on the idea that temporary use licenses, subject to community governance and what we call “self-assessed” fees, are both a fairer and more efficient way of distributing power than conventional ownership. This matters, because the most compelling justifications for conventional ownership rest on the supposition that it incentivizes owners to invest in the things they own. PCO speaks not only to social justice and environmental concerns, but also to the same efficiency concerns that are usually cited to support the status quo.

In this piece, we step back and describe a broad vision for how PCO could help weave a fairer and better-governed society. We’ll begin by comparing conventional ownership and universal forms of communication, discussing how both oppress complex networks as much as they may connect them. We’ll then describe why PCO offers a gentler, less “noisy”, and more “layered” alternative to conventional ownership. We’ll conclude with a few words about how super-powerful AIs might make PCO more workable; and conversely, PCO might make a world of powerful AIs more just and livable.

The Power of Communication

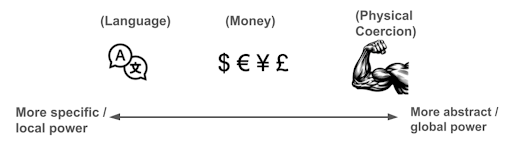

Consider three different forms of communication: language, money, and physical power. These three forms can be understood as having increasing scopes of application, or levels of generality. The first form, language, only directly influences those humans who understand it. Turkish influences most Turkish people, but very few Brazilians. Money is a much more universally-understood form: almost every human adult understands how it works, and can be influenced with large enough quantities of it. Physical power is even more universal. It can be used to influence not only all humans, but also animals, plants, and inanimate objects. It is an extremely universal form of communication.

Universal forms of communication have pros and cons. On the one hand, they can bridge across vast communicative divides, unlocking wonderful connections and mutual gains. But they also have greater potential to be oppressive, “noisy”, and destructive. Think we can’t speak with animals? But we do, crudely, using fences, whips, and food (“carrots and sticks”). Similarly, money forms a communicative link between humans who have little in common, but it also causes us to pay less attention to our local communities. And as people shift into more uniform languages and English-first ways of life, they lose something of their local culture, which is embedded in the dialect.

This is a central challenge for modernity: How can we expand connection without expanding oppression? (Relatedly: Are Networks Democratic?) The connections forged through universal forms of communication are shallow. They are not based on deep mutual understanding, and therefore trample on the complexity—human, cultural, biological, and otherwise—of the networks they connect.

Many flawed ideologies have gained momentum precisely by pretending they avoid this. For example, capitalism promises that we can all interact through money (true), and that there is nothing necessarily oppressive about letting money play this role in society (false). The “information wants to be free” California ideology contends that we can deepen our interconnections using information technology (true), and that this is a costless proposition (false).

To genuinely try to maximize the good of connection while minimizing the bad of oppression, we might look toward principles like “subsidiarity.” It has old roots in the organization of the Catholic Church, but today it is better known for helping to orient the relationship between the European Union and its Member States. It says roughly that authority should rest with the most local and specific institution, unless placing the authority with a more central and general one would ensure greater efficiency in the achievement of mutual goals.

Subsidiarity accords with common-sense moral intuition about forms of communication. We use more universal forms of communication when necessary, but as little as possible. It is better to buy things than to steal them (choosing money over violence), and to resolve conflicts with words rather than money. We prefer to use the most local and intimate form of communication, which is to say the most gentle or layered mode of exerting power, to achieve our goals.

The Power of Ownership

Conventional ownership is another kind of universal power. It is not gentle. It creates global certainty and enforceability around who is able to use, profit from, and control objects—and who is not. In doing so, it too connects yet oppresses a highly complex network: the “layers” of relations around objects.

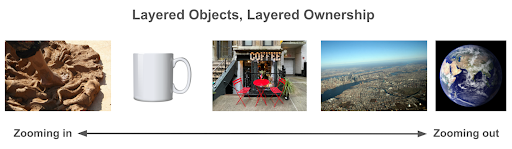

Think about every owned object as having layers, like an onion. When you look at a mug—for example, the one resting on your table in a coffee shop—it does not seem very “layered.” But zoom in on it and you’ll find that beneath its obvious mug-ness it is countless molecules of clay. This is simply a reality, hiding “beneath” the layer of the mug’s outward appearance. And now zoom out, and you’ll see that the mug is only one unit in a set of dozens of similar mugs and plates, which together form a whole: the coffee shop’s tableware. This too is a reality, hovering, if you will, “above” the mug’s outward appearance. Zoom out still farther, and you’ll find that the mug is a minuscule part of the city you’re in. Keep zooming out and you’ll see quite clearly that the mug is a little tiny part of the vast Earth itself.

So it is only from one specific and temporary vantage point—that of a person sipping coffee in a coffee shop—where it truly makes sense to think of the mug as a mug, as opposed to molecules of clay, or part of a city, or any number of other huge and tiny things.

What if we thought about ownership this way? Perhaps ownership rights should be careful not to impinge upon more “layers” than they need to.

Sometimes, ownership rights are already quite parsimonious—no more extensive than needed—and this seems like a good thing. For example, as a cafe customer, the shopkeeper lends you the mug for only a few minutes, while you are using it to drink your coffee. When you’re finished, the individual mug is “reabsorbed” into its other identity, part of a tableware set. Likewise, when a cafe owner buys mugs for her business, she’ll use them until they eventually break. She might then throw them away, letting the clay “reabsorb” into the Earth, in a sense. Neither you nor the shopkeeper has exercised more dominion than you need to drink a coffee and run a shop.

But in many other cases, conventional ownership goes much further than this, giving owners dominion over “layers” of objects that are not connected to the owners’ immediate or active uses. Now, for assets that are purely “artificial capital,” meaning they exist in virtue of the labor that put them together, such ownership can be said to reward virtuous labor. But most valuable assets are partly “natural capital”—they aren’t really put together by labor, but still have value in virtue of the way people can use them. Their value arises from complex and networked processes.

Consider the ownership of land. If you buy land in a city, you can exclude everyone else from using it, indefinitely. As long as you wish, even if you do not use the land in any way, you can call upon the police to exclude others from using it. Then, despite your sloth, you can still sell it at a profit. But that profit cannot be said to reward your virtuous labor. Instead, it is the fruit of the labor of others, who developed physical and cultural infrastructure around the land and thereby increased its value. In this way, land ownership confers a kind of monopoly power by letting the owner impinge upon many “layers” of the land’s ontology—the aspects of the land that have nothing to do with the owner’s use.

Or consider intangible goods, like corporations and ideas.

Most of the value of corporations is intangible—something in the culture and set of relationships that exist among their stakeholders. Viewed in this way, corporate networks are like land parcels: the value of each contract with employees, vendors, and customers is far more networked than it may seem; the value is in how they all work together. Yet conventional corporate ownership extends too far, beyond the layer of efficient management. It is also raw, political power over the communities that constitute firms.

New ideas, similarly, stand on the shoulders of a vast network of prior ideas. For example, the telephone’s inventor (who was it?) needed its critical components like the telegraph and microphone to be invented first, before those ideas could be snapped together, like legos. Yet patents are awarded as desert or incentive to singular entities; no portion goes to the inventors of predecessor inventions, or communities that contributed to the invention. They are idea-monopolies, which prevent others from building on them, and let them be exploited for profit rather than some notion of the common good.

In conventional ownership theory, the state is supposed to recognize and protect all of these other “layers” of objects that conventional ownership would otherwise trample on. Property law does it through property taxes (which are often either much too high or much too low) and zoning requirements (which often impede the public interest). Patent law deals with it by putting a one-size-fits-all time limit on patents, assigning a total monopoly to the individual inventor in that period, and then throwing the rights wide open to everyone forever thereafter. [1] Corporate law relies on antitrust to break up network effects (rather than find ways to make corporations democratically accountable to their stakeholders). The state is supposed to do this for every single asset, every single class of assets, in every single context, in a changing world. This just seems like a hopelessly heavy task. How can any bureaucracy be expected to understand, let alone regulate, all the changing dimensions of all the property rights it enforces? We need to take pity on the state, and find other legitimate, public-interested authorities to share these complex responsibilities.

How Partial Common Ownership Works

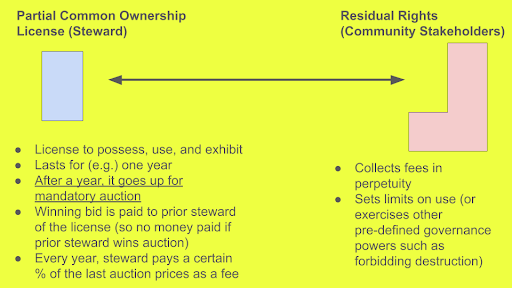

Partial Common Ownership separates the layer of efficient use from other layers of responsible governance, by “splitting” a conventional asset into two new kinds of assets. The first is a PCO license, entitling a steward to act as a kind of owner for a period of time. The second is a PCO residual, entitling its stakeholders to exercise certain governance powers over the asset, and to receive fees from the steward.

The PCO license is an explicitly economic interest, with strong incentives for efficient use and management of the asset. It is a form of equity, making it unlike a rental interest. But unlike conventional ownership, it is temporary. At the end of the stewardship period, the PCO license returns mandatorily to a public or semi-public auction block; such periodic auctions serve as a check on economic power in the same way election cycles are a check on public power. The outgoing steward may bid in this auction and win it—thus retaining possession—or lose the auction, so that possession of the asset passes to the next steward. Crucially, the winning auction bid is paid to the last steward. This means that the steward is proportionately rewarded for any increases in the asset’s value during their tenure, and penalized for decreases.

At the time of each auction, a fee—a percentage of the winning bid—is collected and passed to the holders of the PCO residual. The residual is an explicitly political kind of interest, so it is strictly non-transferable; it cannot be sold. The residual holders’ identities could be defined in different, dynamic ways. For example, in the case of a land parcel, the residual holders might be the (changing) set of people who live near the parcel, since these are the people most harmed by exclusion from the parcel, and the people whose activity most affects the parcel’s value. They are, in a rough sort of way, the parcel’s demos or stewards of its “natural capital.” They would be able to make political decisions about the parcel, like determining what would be acceptable use practices and who would be responsible stewards (consistent with broader fairness considerations).

Two technical points now.

-

PCO, properly calibrated, is more efficient than conventional ownership. The predicted likelihood that an asset’s PCO license will pass to a new steward in each period is called its “turnover rate.” An asset with high-turnover suggests it is more like natural capital (an asset whose value should be mostly shared by a community), and an asset with low-turnover looks more like artificial capital (an asset whose value should flow mostly to its possessor). If the PCO license fee is set at the turnover rate, the present owner has no incentive to either over or underbid—but rather disclose their true, subjective valuation of the license. This incentive alignment unlocks the potential for more efficient markets; even as the PCO residual unlocks the possibility for both returning the value of assets to their local community, and creating community rights to what would otherwise be strictly private assets. This turnover rate is thus a valuable tool for balancing the distinct political and economic imperatives inherent in every asset.

-

PCO licenses are cheaper to acquire than conventional ownership. Because PCO licenses are temporary and require a fee, their purchase prices will be only a fraction of conventional ownership interests. This makes PCO assets more accessible to people with little wealth or capacity to borrow, which could significantly lessen the predominant role of debt and insecurity in the economy. Most of the financial value will be held in the non-transferable and broadly-shared PCO residual. The latter can be understood as a “perpetuity,” or entitlement to the permanent stream of PCO license fee payments. For more detail, see the analysis in part 1 of this piece.

Money Auctions

At this point, we want to state the weakness of Partial Common Ownership systems clearly. To determine when an object should pass from one steward to another, PCO licenses (at least sometimes) use auctions with money. This gives rise to the most principled and compelling worries about the idea. And we’ve already given an account above of why this worry is well-founded: money is a very general form of communication. If we want assets to be governed in a more sensitive, community-based, pluralistic way, it is dangerous to invite another general mode of power to play this mediating role.

But PCO’s critics tend to overlook an interesting way of rescuing the baby from this bathwater: PCO auctions do not need to use dollars or other universal currencies. They can use special-purpose community currencies—which are more like “local” forms of communication. Nor do they need to be open to all bidders. They can use money that is bound within the membrane of the relevant community—what we have called Plural Money.

PCO using public, universal-money auctions is still interesting, even if only as a first step. However imperfectly, it could improve upon the justice and efficiency of conventional ownership interests (which are also, of course, exchanged using universal money). But PCO using gated, local-money auctions is how we ultimately envision PCO systems deeply and attractively transforming ownership relations. Used this way, PCO could form the warp and weft of large-scale asset-sharing systems that distribute gains and govern resources wisely, without sacrificing efficiency or unduly centralizing power.

From Here To There

Some have suggested that Partial Common Ownership could be tested via modifications to property tax regimes. We do not rule this out entirely, but at least in the United States we doubt that existing conventional assets could be transformed into PCO assets without triggering the Takings Clause. This is probably not the best first step toward experimenting with a new mode of ownership.

Instead, conventional assets can simply be conventionally acquired by public or private bodies, and placed into circulation as PCO assets using novel licensing arrangements. This is what RadicalxChange, Serpentine, and our collaborators are working on in the art market. But the PCO infrastructure we are building could be deployed well beyond it. Exciting possibilities include:

-

Urban Wealth Funds could use PCO to support more common-good-oriented development; and put underutilized public assets to use without simply privatizing them.

-

Land trusts and other communities and cooperatives could use PCO to govern shared property, and share the returns, a bit like a mutual insurance scheme.

-

Owners of data and intellectual property could pool their interests by using novel PCO licenses to manage permissions to query (or train AI models on) their information. This is relevant to many initiatives now underway, including the legal resettlement of IP, technical developments around private data sharing, and cultural exploration of AI’s potential.

-

Corporate shares could be split into two assets: PCO licenses (entitling their holders, much like ordinary shareholders, to influence more fine-grained management decisions, such as by hiring and firing leaders) and PCO residuals (governing the more coarse-grained, constitutional/political aspects of the firm, such as changing its bylaws or its charter).[2]

Special investment funds could facilitate all of this. There will be complex legal and regulatory challenges in applying PCO to new regulatory domains—corporate securities, real estate law, data use regulation, etc. This is why the initial barriers are high. But the returns on a fundamentally better matrix of ownership—financial, political, and moral—could be immense.

Pulling The Pieces Together

Partial Common Ownership is complex. It equips us with a new set of dials, such as the turnover rate, the period of time PCO licenses last, and the identities of the residual holders. But we’re not sure it’s much more complex than the ownership structures that already pervade society, and because those dials allow for a more efficient and fair political economy, we think communities will appreciate having them—especially now that AI can help us process much of the complexity in powerful new ways.

For example, AI can help communities set efficient tax rates; calculating turnover rates are data-intensive predictions. AI could also help define and represent the set of stakeholders that should govern and benefit from PCO residuals. Take a land parcel. Its stakeholders should certainly include the humans that live and work near the land, thereby supporting one layer of its value; and it may also include more general actors, such as the city (another layer of its value), or representatives of biospheric or ecosystem-level interests (still another). The set could be defined, challenged, and revised – with all due process – by a judicial test, an administrator, a democratic process, or some combination of those, being assisted by AI. And in negotiating over regulatory-style guidelines—such as what kinds of uses are appropriate, who is eligible to bid to be a PCO steward (while being consistent with broader anti-discrimination rules), and the fees and rates those stewards are subject to—all of these stakeholders could either actively represent themselves, or deputize AIs that they have instructed to pursue their abstractly-defined interests, so the system wouldn’t require any unrealistic degree of stakeholder engagement.

The likely role of AI in a system like this might make some uneasy. We understand that unease, but mostly do not share it, for the following reason. AI will improve and get deployed throughout economic life whether or not we transition from conventional ownership to PCO. And in a world of conventional ownership, it will enable the people with the best command of it to essentially hijack our outdated property rights regime and thereby accumulate an ever-greater share of economic and social powers. In a world of PCO, super-powerful AI might instead enable an ever-finer-grained assessment of who and what ought to share in assets’ passive gains. It represents a redirection of the affordances of the technology toward wise resource stewardship and an egalitarian distribution of power, instead of its compounding concentration.

The early stages of reimagining ownership relations cannot express every aspect of a big vision like this. But we have to start somewhere!

Thanks to Paula Berman, Alex Randaccio, Margaret Levi, Glen Weyl, Anthony Zhang, Victoria Ivanova, Joe Lambke, Andrew Trask, Sophie Steinman-Gordon and others whose insights have informed this piece.

Notes

A whole range of more sensitive compromises might be imagined for intellectual property. For example, circumstances suggest that 20 years is too long a period for some patents, and too short for others. And why not give some portion of the monopoly to the inventors of predecessor inventions; or to particular communities that have contributed to, or stand to be adversely affected by, the invention? Perhaps decision-making rights about a patent’s use should not be in precisely the same hands as entitlements to fruits of its exploitation or sale, so that the patent system could be directed toward some notion of the common good, rather than simply profit. Etc. ↩︎

Nontransferable “residual” rights could be shared between stakeholders as defined by a neutral arbiter: employees, community members, and investors, all vested with financial and abstract or “constitutional” governance rights. The residuals would represent the political, public, and “natural capital” aspects of the relational network constituting a firm. On the other hand, temporary PCO licenses, tradable on an exchange, would entitle their bearers to oversee more fine-grained management decisions. Abraham Singer’s work on the political theory of the firm, and the idea of “corporate justice within efficiency horizons”, sketches a rigorous paradigm within which such PCO shareholding could help legitimize the “political” power inherent in firm ownership without undermining firms’ efficiency imperatives. ↩︎