Evolving a New Public with Web3

Calvin Po, Fang-Jui “Fang-Raye” Chang

January 8, 2024

This series of three articles have been made possible through funding from the Ministry of Digital Affairs (moda). Authored by Dark Matter Labs (DML) and supported by the Frontier Foundation, it has been published in collaboration with RadicalxChange, who supported the editing.

Web3 technology is supporting new ways of organizing that move agency away from its traditional sources, be they governments, international organizations, or multinational corporations, to networks which allow that agency to be exercised at the level of self-organized communities, whether over information, democratic decisions, or assets. This poses a critical question on the evolving role of governments, including Taiwan’s. While certain parts of the web3 community often make it their explicit aim to find alternative ways of organizing without relying on centralized authorities such as governments, we recognize that there are critical roles to be played by the government, especially in the civic infrastructure space where place-based communities and physical assets and resources are concerned.

In the previous part of this series of three blogs, we propose a new framework of ‘decentralized civic infrastructure’ as a web3-native approach for delivering essential capabilities needed for digital participation in society that is resilient and common. In this part, we examine how the government can have a role in transitioning towards this approach. Decentralization makes society more technologically, administratively and socially resilient, and ensures, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, that decisions will be made closest to where they will take effect by citizens who best know the context. Government, as a unique holder of many centralized powers, should use web3 technology as an opportunity to decentralize these powers. Where that is not possible, government should use its centralized powers to allow and encourage decentralized ways of organizing and to allow them to interoperate with existing frameworks.

In our interview with Vitalik Buterin, we mapped out the different roles of the government which impacts the use of web3 in Taiwan, and how they can be leveraged to encourage the development of decentralized civic infrastructure. We expand on these roles below:

-

The government’s role in defining and enforcing property rights

-

The government’s role as a regulator

-

The government’s role in collecting and distributing public funds

-

The government’s role in controlling its borders

-

The government’s role in the legal system and judiciary

-

The government’s role as a convenor

The government’s role in defining and enforcing property rights

Where web3 interacts with physical assets such as property, it necessarily interacts with the government’s role in defining and enforcing property rights and liabilities. The government can also uniquely define new domains for property, such as allocating frequency bands in the radio communications spectrum. It is unlikely web3 will replace the government’s last-resort role of governing property rights. Instead, to support decentralized approaches to managing common assets, the government should consider to what extent it might legally recognize decisions or transactions made about property on web3 systems, such as whether DAOs should be able to own property and other assets (see below for more on how Taiwan’s legal system might recognize DAOs).

The government’s role as a regulator

The government has a role in creating regulations to ensure web3 is used in the public interest. Due to the decentralized and global nature of web3 systems, it is often difficult to regulate them directly, therefore most governments tend to regulate at key points where they interface with actors that are subject to national jurisdictions.

For decentralized civic infrastructure, the government can use its role to offer positive incentives, such as limited liability to DAOs (see below), to encourage compliance with better practices. Similarly, the government’s trusted authority can help establish permissive (as opposed to restrictive) regulatory standards, where citizens participating in compliant web3 projects can be assured of certain protections through its certification, while keeping open the innovation space. One critical area for regulation is to what extent the Taiwanese legal system recognizes DAOs, and what privileges and obligations they may have as legal entities.

Pathways to DAO legal recognition in Taiwan

Rather than leaving an ad-hoc approach to emerge from case law, we propose that the government takes a proactive approach in establishing a framework to clarify how the legal system views DAOs, in consultation with the public and key stakeholders to determine what the public interests are, and to what degree of public oversight DAOs should have.

One possible pathway is for Taiwan to recognize DAOs that are legally recognized by foreign jurisdictions as overseas corporations, and create a register for such DAOs in Taiwan, in a manner similar to the existing register for social enterprises. While this pathway is quickly implementable, we believe there are additional benefits to domestic recognition in Taiwan’s jurisdiction, especially for deepening Taiwan’s economic and social ties with the global community outside of the formal diplomatic system and conventional economic system, and developing the capability to create new economies and innovative value chains.

For an approach to recognizing DAOs as legal entities, we draw on our interview with Primavera de Filippi and COALA’s DAO Model Law, where the government can set DAO compliance standards for privileges that can be uniquely granted by the government (e.g. legal personhood, limited liability for its members), while leaving the innovation space open. Some of the obligations for the privilege of legal personhood and limited liability can be mapped directly from existing corporate law, such as requiring the registration of identity and disclosures of certain information such as annual financial statements. We reiterate two key concepts introduced in the DAO Model Law paper: functional equivalence (where the instruments of the DAO are equivalent to existing mechanisms of corporations) and regulatory equivalence (where the nature of the DAO achieves the same regulatory objectives through different mechanisms). Taiwan’s existing corporate law already offers a spectrum of different entities that are entitled to different privileges based on public interest, from LLCs, to ‘close companies’, cooperatives, foundations and civil associations, onto which different types of DAOs can be transposed.

However, DAOs have many characterstics which are unique to its decentralized form of organizing that have no equivalent, which must be accommodated in a new framework. One of these are DAO ‘tokens’, which are central to DAO operations, blurring boundaries between equity shares, voting rights, and also internal currencies or incentive systems. They risk being considered as securities by regulatory bodies and even being subject to banking regulation. Another issue, as mentioned in the Model Law, is deciding how a DAO’s assets and legal entity are divided in the case of a contentious hard fork. These issues are critical for ensuring interoperability between DAOs and the legal system, and it is important that these contingent scenarios are preemptively considered in line with public policy objectives.

The government’s role in collecting and distributing public funds

While web3 has enabled new forms of funding the public goods such as retroactive funding, the government’s unique role in taxation and administering public spending can also be used to support a more conducive environment for decentralized civic infrastructure, such as by co-funding or providing tax advantages for the development of decentralized civic infrastructure. Government spending decisions can also be decentralized through participatory funding mechanisms. We explore how government can participate in retroactive funding as a model for funding public goods below:

Government’s role in retroactive funding

Retroactive funding is structured on the principle that “it’s easier to agree on what was useful than what will be useful”, specifically for public or common goods, such as civic tech infrastructure. This opens up the co-creation of these goods to a broad range of contributors all across civil society, contrary to centralized systems such as government procurement, which systematically favors bigger actors capable of dealing with the onerous requirements and risks of tendering. Retroactive funding makes contributing to open-source projects more viable through potential payment, while maintaining a performance incentive linked to impact delivered, rather than relying solely on the voluntary efforts of dedicated individuals, and opens up a field of possibility through leveraging the diverse skills and ideas of civil society.

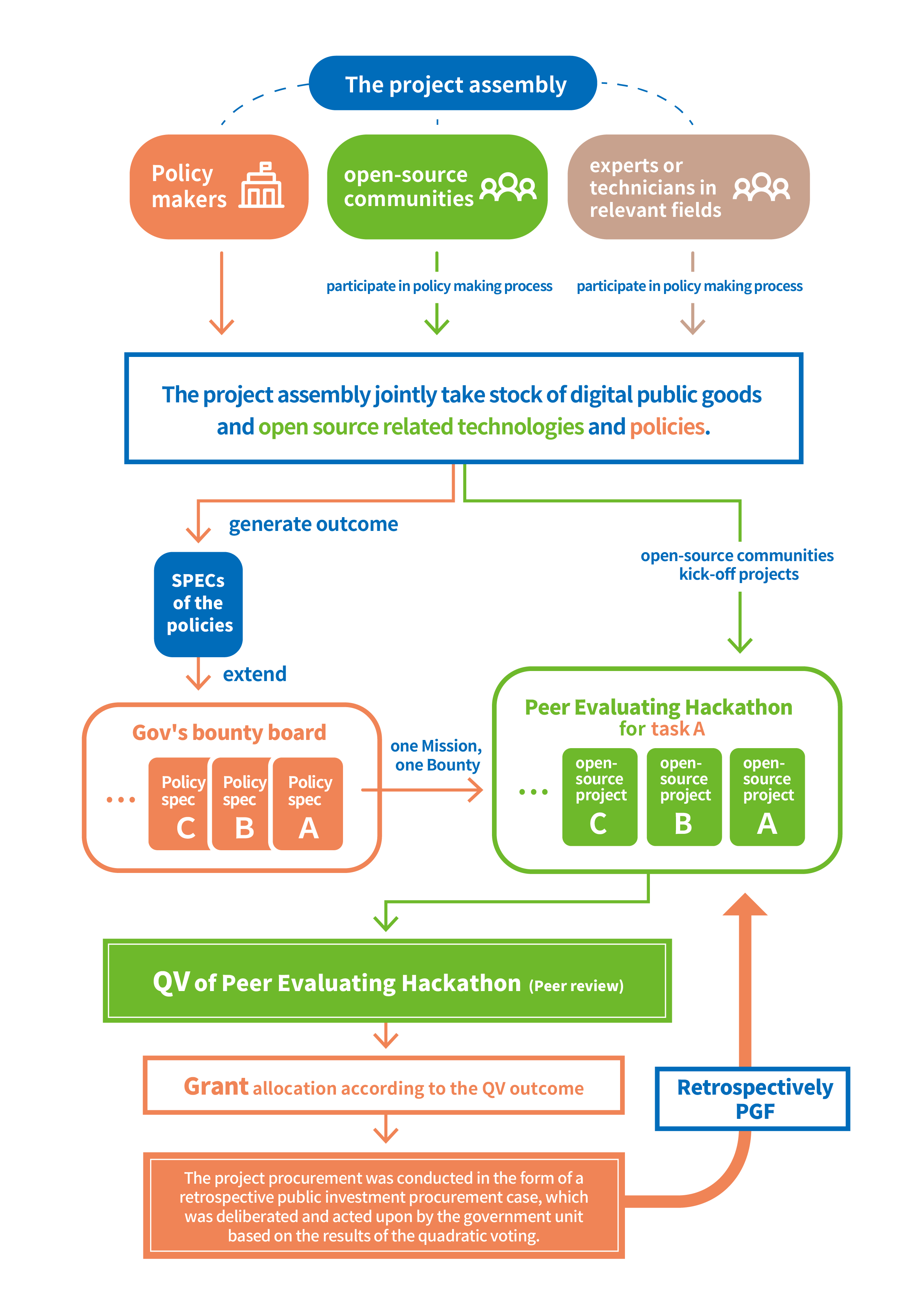

The government can participate in retroactive funding, both as a funder and as part of the collective decision-making. The flowchart above is from the Retroactive Public Goods Funding Recommendation Paper by the Frontier Foundation in Taiwan, which suggests that a ‘project assembly’ could be formed jointly by the open-source community, government agencies, and various stakeholders. This consortium would fully align on the specifications, construction goals, and expected outcomes of the digital public goods. During the development of the projects, blockchain digital certificate recording tools would be used to document the process of individuals’ work, the contributions of each member, and the outcomes at each stage. Subsequently, the same members would organize hackathons to discuss the feasibility of each project, using quadratic voting to select which projects should receive funding, with the government ultimately providing the retroactive funding.

However, central to the retroactive funding is that work is only paid after completion, and the risk of the work not being deemed impactful enough for the community is still borne by individuals. This means that while the ability to contribute is notionally open, in effect this will still be limited to contributors who are able to take the risk of non-payment. We suggest that the Taiwanese government can in addition leverage its public budget to create a more supportive environment for retroactive funding in general, namely through the payment of micro-grants to Taiwanese citizens who do not get retroactively funded but contribute to a minimum threshold, thereby reducing the financial risk of contributing. While this may on the surface reduce the ‘return on investment’ for retroactive funding, there is value added: leveraging this public investment to crowd-in a broader, more diverse base for civic participation is a public benefit in and of itself. Similar arguments have been made for Universal Basic Income: reducing financial risk encourages citizens to invest more time and effort into work which may have no clear route to financial reward, but is a net benefit to wider society, such as the arts, philosophy, and social innovation. The retroactive funding model we propose achieves a similar intention at a much smaller fiscal scale, allowing these principles to be piloted in a sandboxed context of developing decentralized civic infrastructures.

The government’s role in controlling its borders

The government remains exclusively responsible for controlling the movement of goods and people across its borders. This is one of the strategic areas where the government can start to decentralize how it exercises these responsibilities. For example, as mentioned in both our interviews with Glen Weyl and Vitalik Buterin, decisions on when to issue visas for foreign nationals pose an opportunity for decentralization.

Plural Fellowships

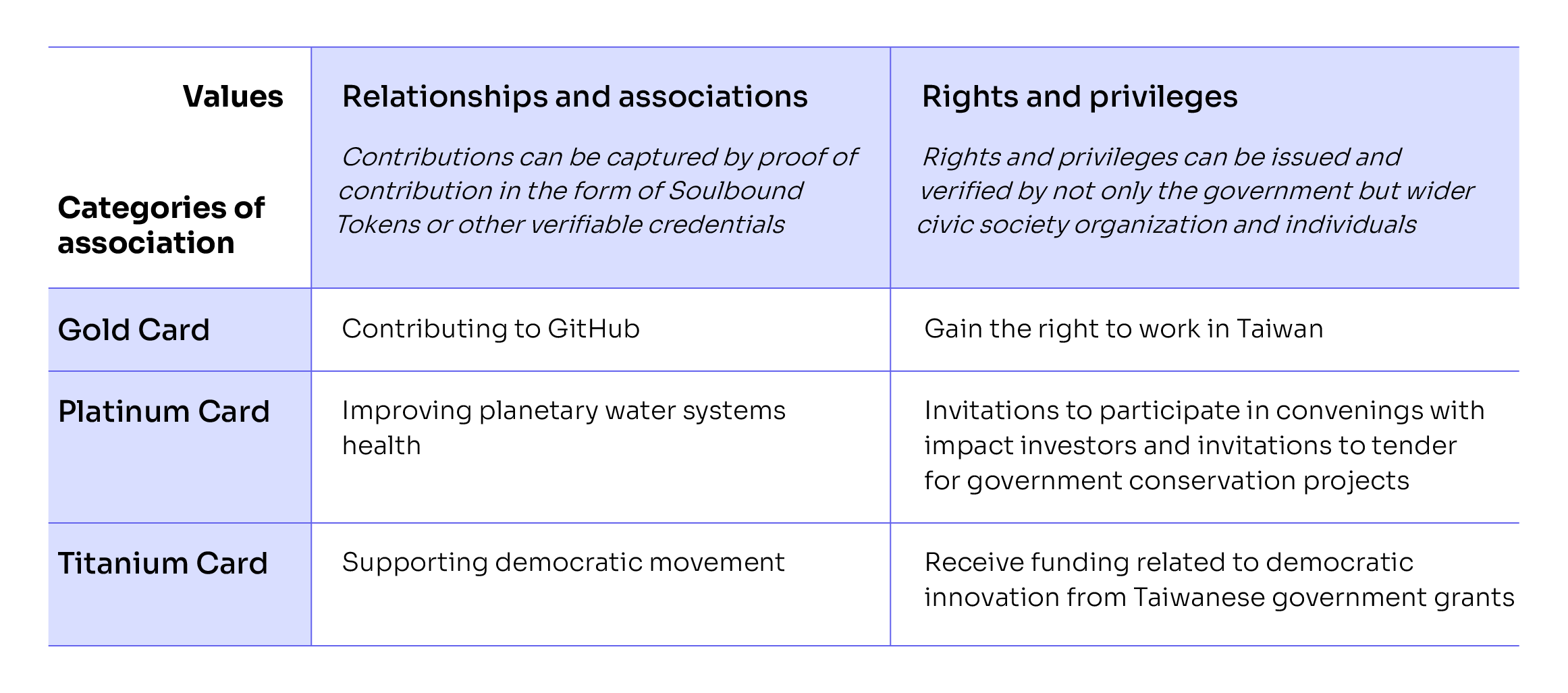

We propose that the government can decentralize its role in granting relationships with Taiwan (e.g. residency, citizenship) by creating diverse new forms of value-aligned relationships and digital associations which we call ‘Plural Fellowships’. These can be linked with a mix of rights and privileges, and created through a decentralized identity system and decentralized credential issuance. This builds on Taiwan’s Gold Card initiative[1], which bases issuance on value-aligned criteria such as contributions to GitHub over the past eight years alongside other types of past contributions and achievements.

Plural Fellowships criteria could include relationships and associations based on social and economic considerations, democracy, and environmental care. Such value-aligned relationships could manifest as credentials (proofs of contributions), be issued and verified not only by the government but also by other organizations and individuals, and be transparently and publicly verifiable with web3 technology. In adopting a socially and contextually constructed identity system with decentralized governance, this approach would foster a more diverse and flexible understanding of identity and belonging, and would allow obligations and benefits linked to residency (and in the future, citizenship) to be disentangled from binary modes of national belonging based on territorial borders. This is an opportunity to make a fundamental shift from bounded to unbounded ways of relating to each other.

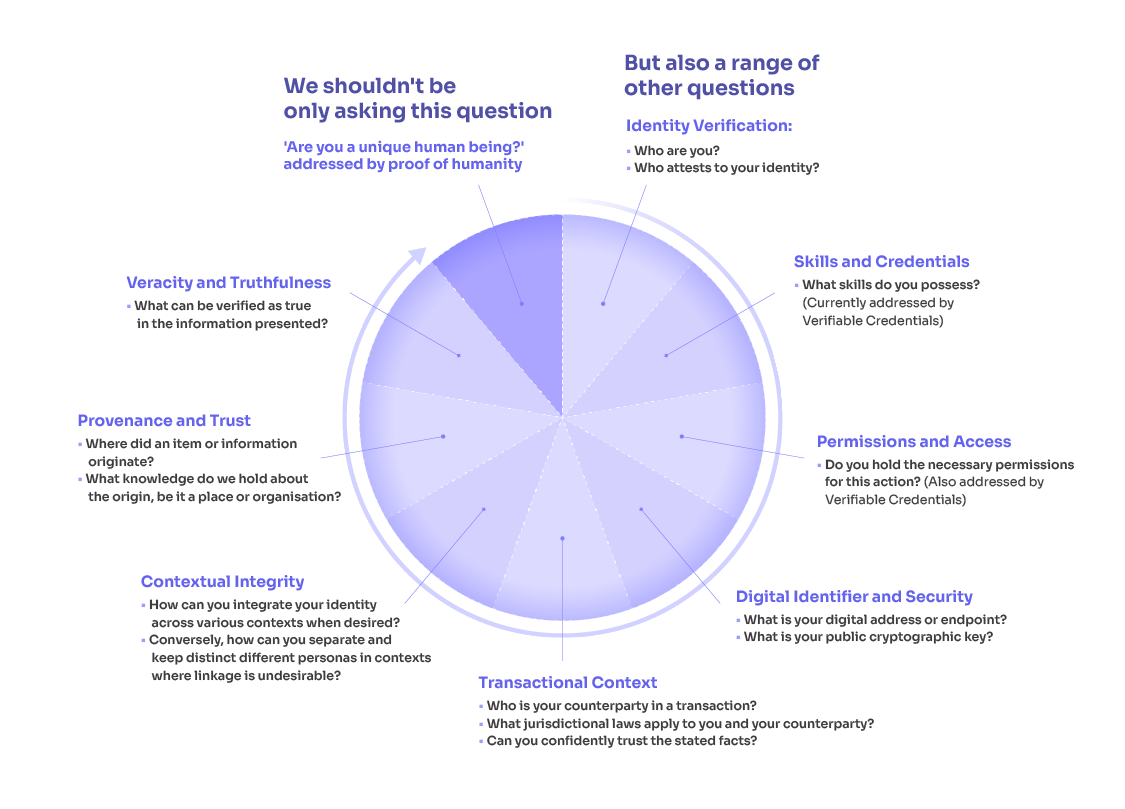

Our concept of Plural Identities draws on ideas from Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang’s book Plurality, in which the authors posit that identities constructed from intersectional social data can recognize that people are not only biological but also sociological beings, and that their social data contains histories and interactions they share with other people and social groups. This means that identity is rooted in a resilient system based on networks of relationships and captures a more holistic image of individuals than simply their intrinsic characteristics. Similarly, Kaliya Young highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of identity that goes beyond technical solutions. She emphasizes the importance of linking new technologies with real-world practices and understanding, rather than trying to create solutions that are only rooted in the technology itself. She proposes that successful digital identity solutions need to balance technological innovation with a deep understanding of how identity works in sociocultural contexts. We need to ask a wide range of questions (see below), not just ‘Are you a unique human being?’

The table below suggests how varying forms of relationships and associations might entitle individuals to different rights and privileges in the Plural Fellowships model, based on the relationships they want to have with Taiwan. Rights and privileges would be earned in accordance with individual contributions, certified by a community of stakeholders. This approach would radically decentralize the granting of citizenship or residency, aligning with the broader goal of fostering a more inclusive and participatory society based on values-based, voluntary association rather than territorial borders.

Plural Fellowships aims to recognise and reward individuals and groups whose endeavors align with Taiwan’s core values and aspirations. This could include contributions in areas such as technology innovation, cultural exchange, environmental sustainability, and social entrepreneurship. By embracing a broader spectrum of value-aligned activities, Taiwan can attract and nurture a diverse range of talents and ideas that resonate with its national ethos and build a strong alliance for resilience.

The government’s role in the legal system and judiciary

Many web3 initiatives still require interfacing with traditional legal systems to operate, where web3 ways of organizing have counterparts in corporate structures and paper-based contracts. There are a limited number of jurisdictions which have adapted their legal systems to web3 systems, with some jurisdictions recognising web3 systems directly, while others offer frameworks with which web3 systems can interoperate. There is an emerging global competitive environment in which web3 projects choose legal jurisdictions conducive to their project aims. The government of Taiwan should consider how it can make its legal system competitively attractive to these projects, especially decentralized civic infrastructures, while considering these measures in balance with the public interest, and legislate to create a “legal API” to allow web3 systems to interoperate with the Taiwanese legal system. As web3 technology will become increasingly subject to the legal system, the government of Taiwan should also consider how literacy of web3 technology, which contains conceptual shifts from centralized tech, can be built up in the legal profession and the judiciary.

Co-developing private international law conventions

Relying solely on domestic approaches towards web3 and law could risk a fragmented and non-interoperable landscape of regulations which may obstruct innovation in the web3 space overall. With the rise of smart contracts, DAOs and DeFi, which all have implications for traditional (cross-border) contractual relationships, principles of private international law should be revisited, including questions of jurisdiction, choice of laws, and enforcement of foreign judgements.

In June 2023, the Hague Conference on Private International Law and International Institute for the Unification of Private International Law (UNIDROIT) have launched a joint working group, HCCH-UNIDROIT Joint Project on Law Applicable to Cross-Border Holdings and Transfers of Digital Assets and Tokens. It reflects a wider need for international collaboration over how international legal principles and web3 characteristics can be made interoperable in general. Taiwan’s participation in these international efforts is not only practical, but as a key backer of decentralized principles, Taiwan’s representation is critical to influencing global efforts such that regulation is done in a way that preserves the technology’s decentralized nature and maintains an open innovation space for web3 technology.

The government’s role as a convenor

The building of successful decentralized civic infrastructure also requires deep engagement and co-development with the citizens who will use it. While mainstream awareness of web3 technology has already grown, a lot of web3 technology is still used by only a small segment of society, due to the learning curve associated with web3-specific concepts and tools. The government of Taiwan already convenes solution builders from across all segments of society, such as through the Presidential Hackathon. To identify opportunities for the development of decentralized civic solutions, the government can also convene solution builders together with stakeholders from specific problem spaces, especially those who are outside of the tech space. This can include experts from fields like social sciences, urban planning, environmental science, and public policy, as well as representatives from non-profit organizations, community groups, and citizens. By incorporating diverse perspectives and expertise, web3 solutions can be more effectively tailored to address the unique challenges and needs of different communities.

Convening web3 and local communities

There are experiments emerging in the web3 space, like Zuzalu (a provocation for a networked ‘state’ and community) and Traditional Dream Factory (a land regeneration project organized and funded using web3 mechanisms), that are exploring ways of using decentralized technology to reimagine how we organize civics. However, these experiments are still ‘niche.’ In order to catalyze the widespread societal change necessary to challenge traditional structures, the government can use its convening power to support these experiments and their scaling. For example, the government can collaborate with TDF by convening the civic tech and local communities in Taiwan to conduct experiments and prototypes that explore the implementation of regenerative finance and governance mechanisms of land-based assets, through the instantiation of a number of regenerative web3-enabled villages and rural regeneration projects. The government could use its convening power to bring together international learning and tools, tech development capability, policy-making power, and local communities participation to realize these experiments.

Pathways towards decentralized civics

In the final part of this three-part series of articles, we explore a series of strategic opportunities to develop use cases and pathways for decentralized civic infrastructure that explore the questions of “identity”, “payment” and “data exchange” in a broader civic sense, including cultural, media, non-monetary and customary relations between humans, more-than-humans and ecosystems, to kickstart a new vision of a pluralistic civics. To be continued →

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to the experts who generously contributed their insights and engaged in meaningful conversations for the development of the paper and these articles. Their expertise and invaluable contributions have played a pivotal role in shaping the essence of this work. We would like to thank (in first name alphabetical order): Arthur Brock, E. Glen Weyl, Jacob Lee, Joon Lynn Goh, Kaliya Young, Mary Camacho, Matt Prewitt, Primavera de Filippi, Scott Moore, and Vitalik Buterin.

We also extend our gratitude to all the individuals who contributed to this paper, both through offering invaluable feedback and actively participating in content creation. Their insights and contributions have been instrumental in shaping this work. We would like to thank (in first name alphabetical order):

Ministry of Digital Affairs: Audrey Tang, Eric Juang, Hao Yuan Ting, Mashbean Huang, Yu Jhen Kuo, and Yue Yin Li.

Dark Matter Labs: Arianna Smaron, Charles Fisher, Eunsoo Lee, Gurden Batra, Hyojeong Lee, Indy Johar, and Shu Yang Lin.

Frontier Foundation: Frank Hu, Lucky Chen, Noah Yeh, Peixing Liao, Vivian Chen, Wei Jen Liu.

Individuals: Gisele Chou, Jeremy Wang, and Jia Wei Cui.

Notes

Regarding the Taiwan Gold Card qualifications, contributions on GitHub are acknowledged as ‘evidence of participation in professional community development activities,’ relevant under the first requirement in the ‘Field of Digital’ section. For further details, please refer to the official Taiwan Gold Card qualifications website. ↩︎