What Are Institutions?

Matt Prewitt

August 2, 2019

Institutions Are Not Just Tools

We commonly think of institutions as having importance in virtue of what they do for us. But their importance arises in equal measure through what we do (or don’t do, or are prevented from doing) for them. In other words, we are not merely institutions’ “consumers”–we are their producers, too. As consumers of institutions, we demand that they deliver us goods like justice, prosperity, and efficiency. But it is through our role as the producers of institutions that those very concepts–and indeed, our lives–acquire meaning. To defend this big claim, I need to explain what I mean. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, an institution is “a significant practice, relationship, or organization in a society or culture; e.g., the institution of marriage”. This is a good basic definition, but I will spend the rest of this piece cobbling together a more precise picture.

1. A Misunderstanding

It is a deep misunderstanding that institutions are mere tools. Rather, they are also the objects of our labor. Put differently, institutions are not like machines which have no function, no purpose, and no reason for existing except to accede to the demands of their operators. Humans serve institutions, as well as the other way around. I am using the term “institution” expansively. I mean far more than just governments, companies, and churches. Families and friendships, too, are institutions. Every cultural practice is an institution. Crucially, this includes work–whether for oneself, one’s family, or a global corporation. Even more importantly, values are institutions. “Kindness”, for example, or “honesty,” are norms of behavior that people articulate through a mixture of individual and social practices. Just like religions, some people participate in these meaning-making practices, while others do not. And some people strive to conform their behavior to them, while others do not. In this sense, values are institutions that both structure and are structured by complex cultural practices, no less than “badminton” or “the Spanish language.”

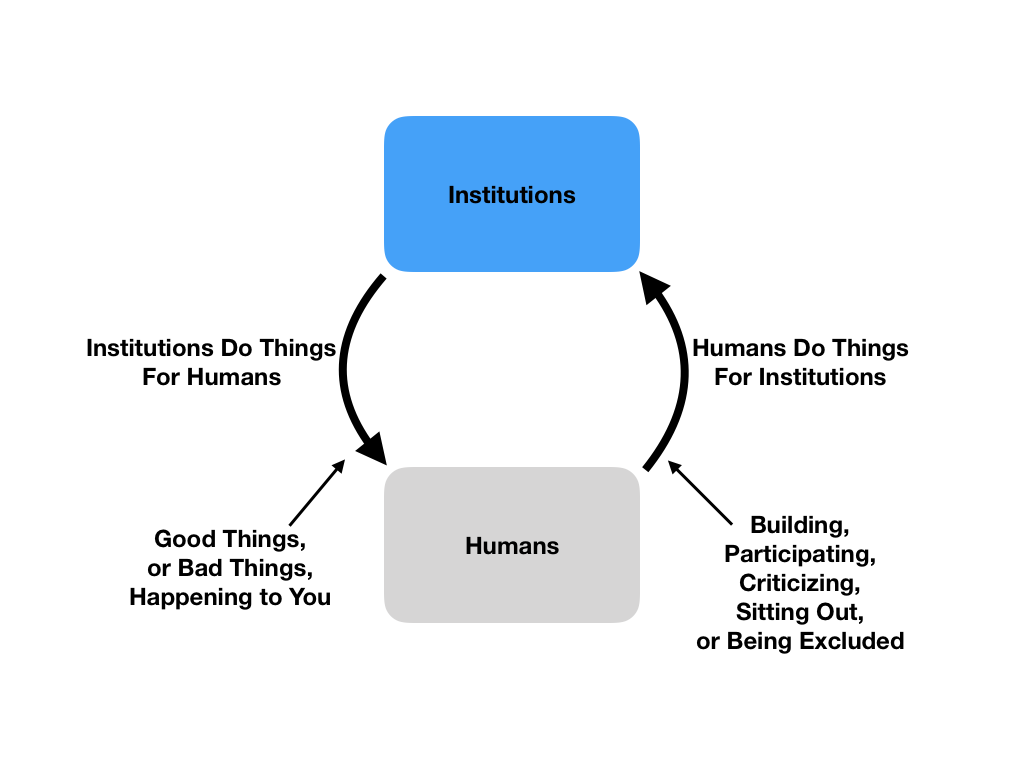

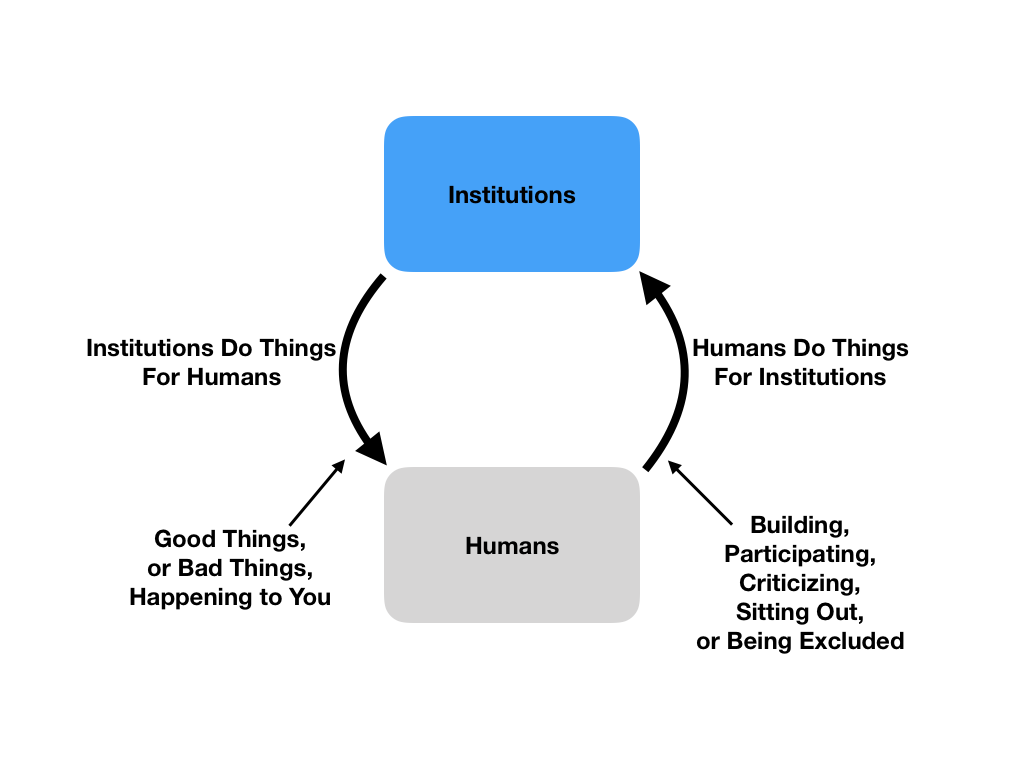

2. Ignoring The Participatory Aspect

By now, you see my point: we stand in reciprocal relationships with institutions. The figure above illustrates that two-way relationship. Everyone knows that institutions act upon us, as indicated by the arrow on the left. But many of us have a blind spot to the importance of the arrow on the right, which signifies that we act upon institutions. When we ignore this arrow–which I will call the “participatory aspect”–we deeply and devastatingly misunderstand what institutions fundamentally are, and why they exist. Worse, we lose the ability to clearly distinguish between good institutions and bad ones. There are countless examples of social pathologies and intellectual mistakes that illustrate the hazards of ignoring institutions’ participatory aspects. But let me start with a particularly salient and contemporary one: I am worried that this particular misunderstanding of the nature of institutions will lead us into a dysfunctional relationship with intelligent machines.

Artificial Intelligence And Social Values

3. A.I. As A “Fiduciary” Of Values…

You’re probably aware of the popular worries about superintelligent machines, but bear with me for a brief retelling.

If machines become many times more intelligent than humans, they won’t need to be malicious to be harmful, and here’s why: They will use their supersmart processing abilities to pursue certain ends or objective functions. And even if these ends are benign, the means to them might not be. (Moreover, we can never precisely foresee those means with our puny human brains–or else we wouldn’t need the superintelligent machines!) So, in the most famous example, a superintelligent machine instructed to optimize the operations of a paperclip manufacturer might decide to exterminate all humans in order to clear the path for more aluminum mines.

One way of describing this worry is that A.I. will not “align” with human values. Even in less floridly apocalyptic scenarios, the worry is definitely coherent. For example, Tristan Harris of the Center for Humane Technology describes the machine learning algorithms now running on Facebook and YouTube servers as, in essence, playing master-level chess games against users with the objective of keeping users engaged. It turns out that in order to keep people glued to YouTube, it helps to recommend increasingly bizarre, extreme, and perverse content. Unhappily, this also radicalizes people by exposing them to false and inflammatory content, provides attack vectors for those interested in disrupting our culture and politics, and–not least–wastes users’ time. In this way the tech companies’ intelligent algorithms are not “aligned” with human users’ values. Their objective is, instead, to keep users engaged, a function chosen for its salutary effects on their share prices.

This worry leads many observers to what I’ll call “fiduciary of values” solutions. Fiduciaries, of course, are institutions that are entrusted to act in the best interests of certain trustees. So, for example, money managers’ fiduciary duties require them to do their best to manage their clients’ money according to the clients’ wishes, while refraining from serving any selfish or misaligned interests.

In the A.I. context, the idea is roughly that we might build intelligent machines with our values encoded as the objective functions to maximize. A naive version of this view holds that we might, in some distant future, instruct a godlike A.I. to “increase human happiness”, hit return, and enjoy. I will not bother to critique that strawman, because there is a much more salient and sophisticated and version of the view out there. The sophisticated “fiduciary of values” view says that machine learning algorithms might, in the immediate future, help people conform their behavior to their own values (instead of manipulating them in the interests of counterparties such as advertisers).

This certainly sounds more attractive than machine learning algorithms manipulating our behavior in the interests of capital. And it is more plausible than a computer figuring out how to rain down happiness that we passively enjoy. However, I think even this sophisticated version flies somewhat close to a serious intellectual error. Namely, it risks ignoring the “participatory aspect” of value formation insofar as it envisions values as relatively static guidelines to which we might better conform, rather than indeterminate things that we constantly strive to define.

4. …And Why It Might Mess You Up

Let me state my worry plainly: If I told an algorithm what my values are, and then it tried to “help” me by manipulating me into conforming to them, I think that might really mess me up.

In everyday experience, trying to conform to one’s values, and trying to define them, are distinct but inseparable activities. It’s common, for example, to offer someone help, aiming to being generous, only to realize in the process that the other person feels condescended to. Such experiences lead sensitive would-be benefactors to revise their ideals and proceed with a more nuanced definition of generosity. This is how people grow. But if we had algorithms manipulating us into conforming to our declared values (somewhat like chess computers pushing our king into a trap), they might cause us to miss the signs that we are being condescending, thus arresting the refinement of our values and definitions.[1]

Now, I do not think it is impossible to build this kind of technology properly. I can imagine machine learning algorithms or A.I. helping us better define our values, as well as helping us conform to them–in a transparent, non-adversarial and non-manipulative way. But it must never ignore the fact that we figure out who we are by figuring out what our values are. Any system that diminishes, distorts or eliminates humans’ role in that feedback loop will be a harmful counterfeit. Humans must engage in the active and never-ending process of defining and refining their own objective functions.

5. A Note About Intersubjectivity

Above, I described an algorithm that purports to help individuals conform to their own values. But values are never actually individual. No individual arrives at their values in isolation.

Take the example of generosity. If I contended that stealing food from starving babies in order to enjoy a pleasant snack is a good example of generosity, I would be wrong. So wrong, in fact, that no reasonable person in my society would agree with me.

Following this example, we might be tempted to conclude that “true” values are not what individuals say they are, but what groups say they are. But of course that isn’t right, either. History is littered with huge groups going morally haywire, while a few individuals and subgroups retain clarity.

The way out of this puzzle is to understand that values are social, or “intersubjective.” They are a matter of opinion, but not of individual opinion (alternatively, they are facts–but social facts rather than pure objective facts). Human societies have (or more accurately, are) complex mechanisms of aggregating viewpoints into loose social consensuses. So while individuals may not seriously declare the moral truth, they may participate in and co-create the relevant social truth-finding institutions.

This is an important point. When social institutions work well, dissenters do not merely interface with them, like customers speaking to clerks through glass. They partially constitute them, via protest, litigation, newspaper columns, dinner table arguments, or whatever else.

With that said, many institutions are quite lousy. Some, for example, systematically deprive women or minorities of a voice. Others deprive everyone of a voice, save some dictator. Still others bury the voices of valuable dissenters in a maze of bureaucracy. And still others amplify nonsensical viewpoints in response to perverse incentives, such as because nonsensical views are captivating to audiences, or useful to corrupt leaders.

All dysfunctional institutions, however, share a common feature. They cut people out of the loop, misunderstanding or denying their own participatory nature. They are insensitive and unresponsive, so that some or all people stop trying to shape them. You see this dynamic in dictatorships, apartheid-type societies, and gridlocked bureaucracies.

A.I. might bring about this same phenomenon in weird new forms–for example, cutting everyone (even the dictator) out of the loop, or cutting people out of their own internal loops. Can we, as individuals and communities, constitute A.I. the way that we have constituted successful human institutions in the past, like families and religions? This is the real question. Just as with a dictatorship, the worry isn’t only that A.I. will do bad things. The deeper worry is that it will sideline us from the life-affirming process of constructing our values, our communities, and ourselves through shared institutions.

Early Modern Problems

6. From Gutenberg to Turing

I’m really only using A.I. to illustrate a much broader argument. For the problems it threatens are not new: Emergent information technologies have been “cutting people out of the loop” of institutions at least since the dawn of the modern era. Let me explain.

For many millennia, labor and value tended to stick together. Where there was a thing of value, the labor that made it had touched it. An arrowhead? Somebody carved it. A basket? Somebody wove it.

But then technologies arose that permitted easy copying. That changed everything. When Gutenberg started selling printing presses in 1492, people could suddenly sell books that they didn’t write. Thus, printing press owners (capitalists) gained power. Some authors managed to claim a healthy share of the new pie, but not all. In other sectors, labor did even worse. Basket weavers, for example, were pretty much wiped out by basket factories.[2]

In other words, industrial copying technologies attenuated the participatory aspect of many cultural and economic institutions. From the perspective of laborers, hard work in certain crafts no longer necessarily paid well. Meanwhile, passive ownership of copying equipment (like printing presses and assembly lines) became more potentially lucrative. So work became less meaningful, both in theory and in practice: Think of the differences between an artisan and a factory worker. And from the perspective of consumers, paying for goods became less likely to reward meritorious labor, and more likely to benefit copy machine owners. So consumption, too, became a “noisier”, less meaningful lever for expressing one’s values.

These attenuations did not weaken the arrow on the left side of the diagram above–namely the outputs of economic institutions. The outputs remained strong, and the industrial economy produced great material wealth. But the prevalence of copying diminished or degraded human participation in many economic activities, by separating labor from value. This contributed to many social and psychological maladies around the time of the industrial revolution.[3] So ignoring, attenuating, or severing the participatory aspect of institutions is nothing new.

7. What Is Intellectual Property Law Really Doing?

In fact, people noticed this problem as early as the 1600s. Back then, it seemed wrong that printing press owners could simply get their hands on a great text, and cut the author out of the spoils. Therefore, the Parliament of England passed the 1662 Licensing of the Press Act, “for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulating of Printing and Printing Presses.” It was a predecessor to the first true copyright act, the 1710 Statute of Anne.

We all basically know what copyright law does. But try this on for size as a slightly different way to think about it. As technology develops, labor become easier to convert into information. And as it gets easier to convert labor into information, laborers lose the natural monopoly on the fruits of their labor given by the embodiment of their labor in physical objects and services. This leads them to participate less in valuable social institutions like authoring, thus impoverishing not only readers, but authors and would-be authors. So as technology enables ever more forms of labor to be converted into information, the “participatory aspect” of many institutions gets severed or attenuated, radiating ill effects of the kind I described in the last section.

We’re accustomed to thinking of intellectual property law as a device to incentivize authors, inventors, and the like. That account is accurate, but only describes one side of the coin. IP also limits the use of copying technology to stop it from displacing humans from human institutions. Thus, in 1662, the English state flexed its coercive power to stop certain uses of printing presses, in order to protect the participation of authors in authoring.

Obviously, states can and do misuse this coercive power, such as by protecting copyrights for an absurdly long time, or granting patents to obvious inventions and broad ideas. But even as a critic of intellectual property in its many dysfunctional incarnations, I can appreciate the basic wisdom of the enterprise. IP acknowledges that copying technology undermines a good thing: The natural monopolies of laborers on the fruits of their labor.

Quite reasonably, IP seeks to create artificial monopolies for intellectual laborers, to replace the natural ones they have lost. In so doing, however, it brings the regulation of technology into the realm of politics. And politics, of course, is itself comprised of institutions. State power is only as legitimate as the values and institutions that guide it. The efforts to regulate technology need to be characterized by the values they are ostensibly trying to preserve: broad participation in power.

So we are still grappling with the same problem that Queen Anne’s Parliament tried to address more than 300 years ago. The unlimited use of new copying technologies threatens to impoverish human institutions by preventing the humans that participate in them from receiving the value of their labor. The remedy must involve some limitations on the uses of those technologies, but the precise contours of those limitations will be illegitimate and counterproductive unless defined by genuinely democratic means.

Democratic Technology

8. The Unavoidableness of Democracy

We know we need to make political decisions about technology, like Queen Anne’s Parliament did. And we know we need to do so democratically.

But we are paralyzed, because we also know that our democratic mechanisms don’t work. People vote in strange, irresponsible ways that fail to capture our collective values. We routinely see righteous minorities oppressed by apathetic majorities, and conversely, reasonable majorities bullied by narrow-minded, hyper-zealous factions. It’s a mess.

That’s why I believe in the critical importance of actually improving democracy. Only by improving our democratic systems will we gain the confidence to make more and bigger decisions democratically. And only by doing that will we ensure that everyone has a voice in the future.

Hence my enthusiasm for Quadratic Voting and related ideas. QV isn’t a panacea, but it is a meaningful upgrade to democratic systems that haven’t been improved for more than 300 years. And even a small upgrade could have huge and cascading positive effects. By helping ballots more accurately capture our collective values, it could in turn increase engagement, which could give us the confidence to democratize our most important institutions, like technology. It could change everything.

9. Quadratic Voting and Legitimacy

The point of democracy is to make power legitimate. What does that mean?

Wherever the governed and the governor are identical, it is hard to doubt the legitimacy of power. But where they’re different–that is, where Community X is governing Community Y–legitimacy is questionable for all the reasons I’ve been articulating. Healthy institutions are things to participate in, not things to obey or to receive handouts from. Democracy increases legitimacy by handing power to the governed.

But this only makes sense if the governed can actually express their values, richly and coherently, through democratic mechanisms such as voting. And here’s the thing. Straightforwardly asking people what they value is not a very good way of finding out the answer. As any sports better or stock trader knows, real honesty arises when something is at stake.

This is a valuable insight that might greatly sharpen the quality of democratic participation. One way of incorporating it into democratic systems would be to make people pay for their votes. But that, in addition to being anti-egalitarian, would place the winners of a governed game–the economy–in charge of the rules. It would bring democracy out of accord with the legitimacy criterion I sketched above, namely the identity of governor and governed. Everyone in a democracy needs to have the same voice.

Quadratic voting gives everyone an equal voice endowment, but asks them to pay for the votes in a currency other than money. Namely, voters buy influence on each issue by sacrificing their influence on other issues. And when voters concentrate their influence on single issues, thereby increasing the probability that they will be pivotal to the outcome in those issues, they pay–again, in the currency of voice–the cost of the externality that imposes on other voters. It is a vastly richer institution than the clunky old ballots democracies have been using for the past few hundred years.

Conclusion

Institutions are not mere service providers. They are also things that we serve, and in so doing we define our values and create meaning for ourselves and our communities.

One of the principal institutions in our lives is the institution of work, or value creation. New technologies often attenuate labor from the resultant economic value, thereby weakening our practical ability to generate meaning and express our values through participation in both labor and consumption.

To prevent technology from impoverishing us in this particular way, we need to place certain limitations on its uses. But these limitations will be illegitimate, and will reproduce the problems they seek to address, if they are not democratic. To meet this challenge, we need better tools for democratic decision-making.

Overcoming our 21st-century technological challenges will not be easy. But the path forward leads through more and better democracy.

[1]: The example above depicts someone who incorrectly believes that their behavior and values are aligned, and then discovers their error. But it is equally interesting to consider people who believe, correctly, that their values and behavior are not aligned, such as a meat-eater who is totally persuaded by the moral arguments for veganism but isn’t ready to quit bacon. Presumably, such people would be the main beneficiaries of A.I. “value fiduciaries”. Yet I see serious risks. When our values and behavior are misaligned we actually have three choices: (1) improve our behavior, (2) live with cognitive dissonance, or (3) compromise our values. A.I. value fiduciaries might hasten some people’s migration, felicitously, from (2) to (1). But in other cases it might hasten peoples’ movement from (2) to (3). For example, if users tire of gruesome PETA videos that their phone makes them watch whenever they buy bacon, they might start coming up rationalizations for meat production–taking the “back door” away from cognitive dissonance, if you will.

This problem is, in principle, solvable. But I still see it as a major risk because in my opinion, far more harm is caused by people who choose option (3) than those who remain patiently with option (2) until they are ready to make a change in their lives. People who choose option (3) acquire a vested interest in not being pushed back into the cognitive dissonance of option (2), so they tend to loudly and vigorously defend their compromised values. In so doing they mislead others looking for easy solutions to moral dilemmas, degrading our shared values. Value fiduciary A.I. might even amplify that harm by letting people who chose option (3) feed compromised values back into their objective functions.

[2]: Please do not think I have some naive nostalgia for the past. I do not. The pre-modern era had other problems, including brutal feudal oppression. Highlighting problems unique to modernity is not the same as saying that the preceding era was overall better.

[3]: See preceding endnote. See also Emile Durkheim on anomie. Durkheim wrote about the idea of anomie in his famous 1897 study, Suicide, which chronicled and examined rising suicide rates in industrial Europe. He defines anomie as a sense of normlessness arising from a mismatch between personal or local norms and broader social norms, resulting in a lack of “legitimate aspirations” and a situation in which people do not understand where they “fit” in society. His account about the causes of anomie focuses on the mechanization and regimentedness of modern economic life. I am offering a subtly different but not contradictory account of the same phenomenon.