Distributed Value Accounting for a Post-Capitalist Planet

Sarah Manski

March 14, 2019

“The distance between today’s industrial systems and truly sustainable industrial systems — systems that do not spend down stored natural capital but instead integrate into current energy and material flows — is not one of degree, but one of kind.”

- David Roberts

Introduction

Those activists, artists, entrepreneurs and scholars drawn to RadicalxChange, including myself, are looking for new ways to use technology and market mechanisms to reduce inequality, environmental destruction, and social alienation. The common vision here is one of a post-capitalist society in which the people cooperate to construct more fulfilling and regenerative economic relations. This radical ‘sociotechnical imaginary’ of how we might uses science and technology to produce a collective vision of a positive future, is shared on a global scale by a rising movement of technologists who are constructing prefigurative applications allowing humanity to cross the bridge to a post-capitalist economy.

A significant component of the vision requires a radical shift in value accounting enabled by new technology. Distributed ledger technologies (DLTs), such as blockchains, are opening up a possible future of a wave of infrastructure decentralization within industrial production. This is possible because DLTs remove the need for central intermediaries to validate transaction between parties, which instead place their trust in the disintermediated system software. DLTs can be designed as a new unencloseable (non-commodifiable) medium of communication which could lead to radically new forms of cooperation, organization, and governance. Yet these revolutionary possibilities will not be realized unless people consciously and strategically design systems altering “value” as it flows through financial, service and national infrastructures.

In this article I offer a vision of a post-capitalist society that may be created through socio-technological innovation. Central to this transformation is a shift in the concept of “value” as it exists in contemporary capitalism toward a new role for value in a decentralized system of economic relations. The capitalist economy is experiencing a crisis of value – rampant destruction of ecosystems, oppressively meaningless employment, extreme poverty, rising xenophobia – the pathological values of global capitalism are diametrically opposed to the cooperative values of humanity. The path that leads forward to a system of sustainable and humane value, must combine available technology and the existing cooperative movement to create a world of open cooperatives and digital commons.

What are technologists building?

How might we recognize value outside of capitalism?

“In materializing, objectifying, and displaying the value of acts, the publicity and formality of ritual approximate the way the market objectifies the value of work but making the consequences impossible to commoditize. One might even say that ritual de-commoditizes value.” Michael Lambek

In the quotation above Lambek discusses how humans have used ritual to define community value. Ritual returns a sense of the sacred to human activity, while commodification alienates humans from their labor. If we want to move to a cooperative, post-capitalist planet, then we must decommoditize human energies by treating our productive activity as sacred and ethical. C.B. Macpherson argued human activity is ethical when our internal and external motivations for performing acts are in alignment, “Man is not a bundle of appetites seeking satisfaction but a bundle of conscious energies seeking to be exerted.” To the greatest extent possible value must be incommensurable.

How could we even begin this process? All technology opens new pathways and forecloses others via the operation of technology’s ‘material agency.’

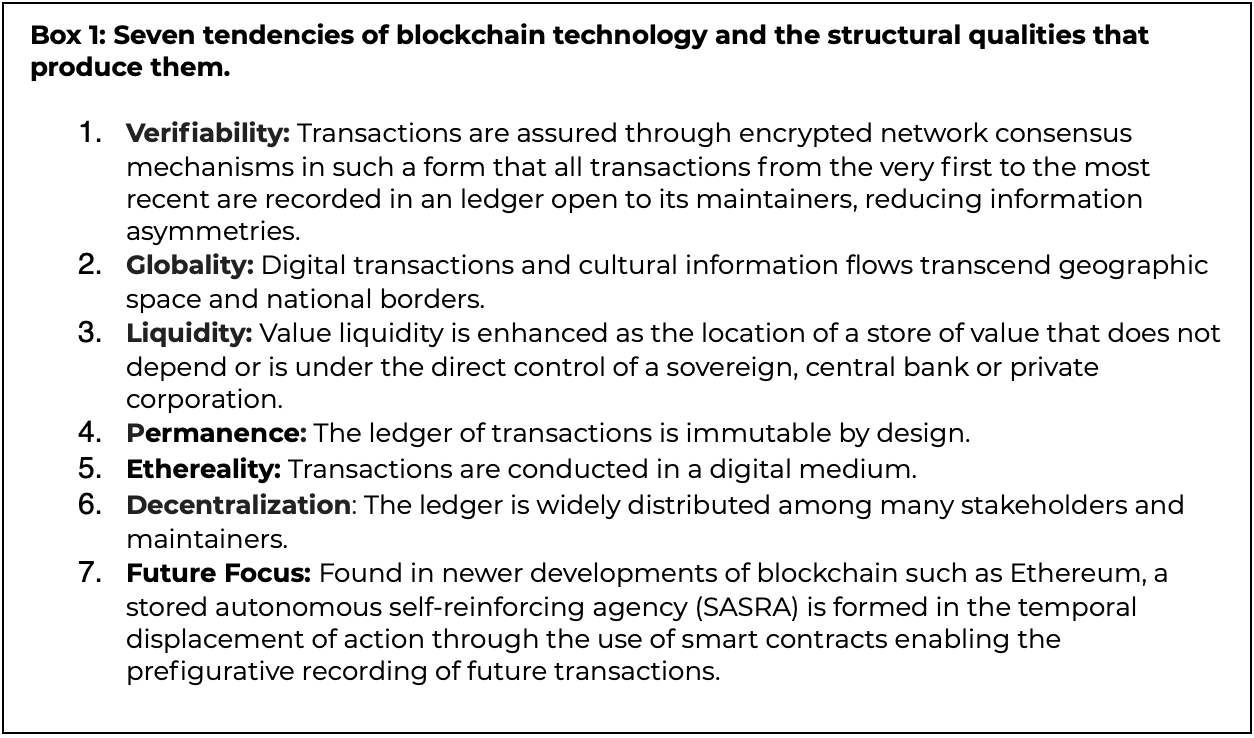

Blockchain is an emergent technology that various scholars have argued is materially transformative. Its design is intended to enable the transfer of value with increased transparency, efficiency, and security. Technologies in general have tendencies that are materially inherent and not simply produced by social context. This is because a technology is itself a structured set of relations that enables or constrains different sets of possibilities. The intended tendencies of blockchain technology are directly available in blockchain code and seven such tendencies are listed in Box 1.

Some of these tendencies would appear mutually contradictory if manifested in an earlier technology, and suggest that the embodiment of previously contradictory tendencies within the same technology can be understood to signal its revolutionary character. It could be that the material agency of distributed ledger technology will lead toward the construction of an economy based on distributed value accounting. Distributed value accounting (DVA) is an economic system of production facilitated by digital technologies which allow for the collective creation of value and the cooperative circulation of wealth through an open community. In this economic system, humans are not simply consumers. The basis for cooperation is mutual aid; the voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for mutual benefit, in which each commoner shares what they can contribute and what they need. The community holds collectively shared beliefs regarding value and engages in the development of a new basis for its calculation and new accounting standards.

Distributed value accounting will be the key to valorizing what Yochai Benkler and Helen Nissenbaum (2006) call Commons-Based Peer Production (CBPP), a new mode of production in which individuals form communities on the basis of creating shared value through open contributory systems. Participants in a CBPP system govern their common work through open input participatory practices and create shared resources for the common good.

There are people working on DVA-type systems throughout the world, but sensorica.co, started in 2011, is the current gold standard for resource accounting/value flows, as they developed Network Resource Planning (NRP) as the first example of an “open value network”. There are a number of forks of the software in use by other groups, including freedomcoop.eu.

What is a post-capitalist society?

Just as major financial institutions, government economic planners, and venture capitalists are motivated by the new possibilities to maximize their institutional advantages using technologies, so too are a growing movement of social entrepreneurs, cooperatives, and activists who are using technologies in pursuit of cooperative ownership and management of wealth, or what I term a technological commonwealth.

The purpose of a commonwealth is to develop, “community economic institutions which are egalitarian and equitable in the traditional socialist sense and controlling productive resources for the benefit of all, but which can prevent centralization, and, which over time can permit new social relations capable of sustaining an ethic of individual responsibility and group cooperation which a larger vision must ultimately involve”. Thus, a commonwealth might be thought of as an economic project that aggregates, distributes, and governs capital at multiple levels and on a cooperative basis. A ‘technological commonwealth’ is a commonwealth enacted through the use of advanced exchange, communication, and decision-making technologies. The specifics of what a technological commonwealth would look like in practice are beyond the scope of this blog, so if you would like to learn more please explore these excellent free e-books written by the folks at the P2P Foundation.

What is value in capitalism?

Capitalism is a system in which those who hold ‘capital’ rule. Michael McCarthy describes four foundations of capitalist society:

- Production is for exchange (not consumption) and profit (not barter).

- Productive assets are privately owned by a small minority (capitalists).

- Most people need to work for someone else to survive (wage labor).

- There is a monetary system that produces bank-credit money (centralized monetary system).

What does this mean for the nature of value in capitalism? Capitalist markets recognize profit as value and the things that enable the production of commodities as value. Thus, we are required to develop a new way to recognize value if we want to live in a world where humans and other living systems thrive.

The terms ‘value’ and ‘wealth’ are often used interchangeably, but this can lead to confusion. Adding to the opacity is that mainstream economic theory does not have a stable theory of value. For neoclassical economists, value is subjective, making it a function of whatever the market says it is. Karl Marx, in line with a previous generation of classical economists, identified value more concretely, and still offers the most useful concepts for understanding value and wealth, and for recognizing how essential it is to distinguish wealth from value, and productive labor from unproductive labor. Marx’s labor theory of value holds, among other things, the following:

- The source of real wealth in society includes natural resources (land, water, wind, metals from the Earth, trees, etc.) together with human labor (physical, intellectual, social); such wealth is recognizable by its use value (that is, the value of its potential use to human beings or to natural systems).

- However, within capitalism, what has value in the market is only that which can be used to produce commodities which can be sold for profit; this form of value is called exchange value.

- Because the production of commodities for sale requires human labor to transform nature into exchange value, and because labor is necessary to produce the surplus value that capitalism recognizes as profit, the taking of profit involves an extraction of value from both human labor and nature.

- Therefore, capitalist social relations only include natural wealth in its value calculus for the production of commodities, yet capitalism is entirely reliant on natural systems. The costs of commodity production are externalized to society as a whole.

- Money is used as a universal commodity and bearer of value; this is problematic in that it liquifies value and causes the human and natural sources of value to lose their multidimensionality.

Marx envisioned a mechanization process of what we now call modernization by which scientific knowledge and technology come to be more important factors in the production of wealth than less intellectual manual labor:

“The surplus labor of the mass has ceased to be the condition for the development of general wealth…Capital itself is the moving contradiction, [in] that it presses to reduce labor time to a minimum, while it posits labor time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth…Forces of production and social relations – two different sides of the development of the social individual – appear to capital as mere means, and are merely means for it to produce on its limited foundation. In fact, however, they are the material conditions to blow this foundation sky-high.”

To restate the passage above, technology embodies the general productive power of human knowledge, producing wealth with human labor only required to regulate the production process. The surplus labor of the mass of working people is no longer the main condition for the development of general wealth. Instead, the general intellect becomes a direct force of production. So that’s where we are now.

Why a crisis of value now?

The world in which we live is in a period of transition. Great masses of people have lost faith in the economic, social and political systems they had previously relied on to provide a good life. Jurgen Habermas called such a period one of ‘legitimation crises,’ wherein people lose confidence in the “steering mechanisms” of society. Antonio Gramsci called such a historical moment one of ‘interregnum,’ in that “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” The morbid symptoms visible today include rampant ecological destruction pushing past planetary limits, societal fragmentation and individual alienation, jobs lost to automation, productive undercompensation due to zero-marginal cost reproduction, and heteromation, the process through which human interaction is increasingly mediated by technical systems silently extracting economic value.

As the collective power of labor has declined and nation states impose austerity and other measures breaking previous social contracts, we have seen a generalized return to what Silvia Federici and others refer to as ‘un-free’ labor. Federici points out that the globalization of the world economy and the corresponding freeing of capital, combined with the computerization of work will, “not only destroy those ‘pockets of communism’ that more than a century of workers’ struggle had won but undermine our ‘production of commons’”.

Already, the pace of technological change may have moved beyond what society can healthfully absorb, leaving people extremely disoriented as new societal and organizational forms rapidly emerge and then, before these forms fully mature as a culture, give way to the next set of technocultural formations. Social scientists from Durkheim to Karl Polyani have made it long understood that hierarchical social orders can be rapidly destabilized by either economic collapse or through the accrual of sudden economic wealth. If the past can be used to imagine the future, our global future will be experienced as an accelerating period of constant disorientation and destabilization spurring radical political, institutional, economic, and social change. We have the power to forge another path forward.

Our current social, political, and economic institutions were created to protect and facilitate the growth of industrial capitalism. Yet the technological basis of industrial capitalism has given way to the digital economies of a post-industrial world. As profit becomes disconnected from production, people are now rising up and demanding that more than profit be valued. Our determination of what is valuable is indicative of how societies are able to stay together; value is our collective social capacity and our interdependence upon each other.

Conclusion: The Value of Value

Hardt and Negri argue that in the new technology-based economy, directly socialized, immaterial (digital, knowledge) production sets in motion the political and social relations necessary for the creation of a commonwealth, “A democracy of the multitude is imaginable and possible only because we all share and participate in the common.”

Commoners, democracy activists, and technologists are now building a coalition of technologies and broader publics to redesign the accounting of value. They share a strong desire for a transition to a cooperative, fulfilling and regenerative social and economic system beyond capitalism. Technology can deliver or than one possible future. The excess capacity for social cooperation enabled by distributed ledger technologies is necessary to be able to move to a post-capitalist planet. We need to work with each other cooperatively, as Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s direction that “We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society”.

To accomplish this transition we will need to develop a new way to recognize intrinsic human and ecological value. I believe it is possible to combine our emerging distributed technologies with the ongoing cooperative movement to create a world of open cooperatives and digital commons for all of humanity to share. I am thankful that I am not alone in seeing these possibilities or in demanding and seeking to build a world of rejuvenation and abundance for all.